Tuklas

Isko Andrade/ Michelle Ballesteros/ Lawrence Cervantes/ Denmark Dela Cruz/ Carlo De Laza/ Harry Mark Gonzales/ Mark Leo Maac/ Marvin Quizon

November 25 to December 20, 2017

Artistic talent cannot exist in a vacuum. The artist working in his cell, waiting for inspiration to strike and, when it does, paint his grandiose vision in a flurry of brushstrokes is a tired trope in art history. Even the most hermetic of artists (Van Gogh comes to mind) had some support. More so in this contemporary moment in which the creative climate encourages collaboration, openness, and critique. To be an artist today is to be receptive and responsive to ideas, to be implicated in a web of relations which, one hopes, will deeply inform, energize, and improve his practice in more ways than one.

Tuklas offers such a space in which a beginning artist can test his ideas and be a part of a community. Started last year by Renato Habulan and Alfredo Esquillo, Jr., it envisions to discover, mentor, and train a new crop of artists that can combine the rigors of craft with the depth of perception awake to the ills of society. Isko Andrade, Michelle Ballesteros, Lawrence Cervantes, Denmark Dela Cruz, Carlo de Laza, Harry Mark Gonzales, Mark Leo Maac, and Marvin Quizon compose the first batch and whose works Eskinita Gallery is proudly presenting in this exhibition.

Almost every week, these artists would meet at Eskinita Gallery for studio and critiquing sessions. During discussions, they articulated and interrogated what they hoped to achieve in their works. Their mentors, as well as fellow Tuklas members, provided feedback, in a collective spirit of encouragement and support. They shared the belief that any sort of artistic vision, no matter how fully formed, could be made—and executed—better.

While the classroom experience remains as a powerful intervention with regard to the instruction of the artist (something that Tuklas is, albeit informally) mentoring has a more direct and lasting impact. For one, aside from delivering a more focused transference of material, technical, and conceptual know-how, it addresses issues surrounding artistic practice and production that the mentors have dealt with and can speak credibly about. The importance of hands-on learning through the studio sessions is incalculable. Mentoring also conveys that “they are all in this together,” doing away with the hierarchic structure present in the conventional teacher-and-student relationship.

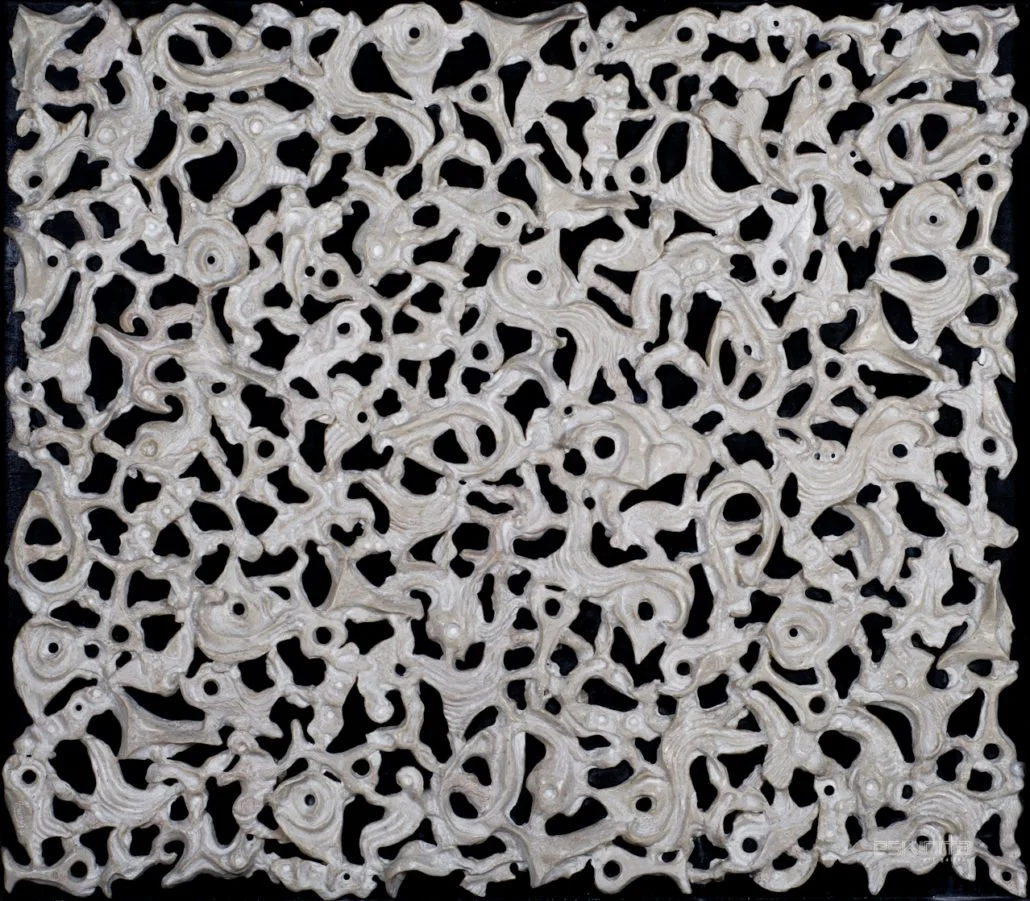

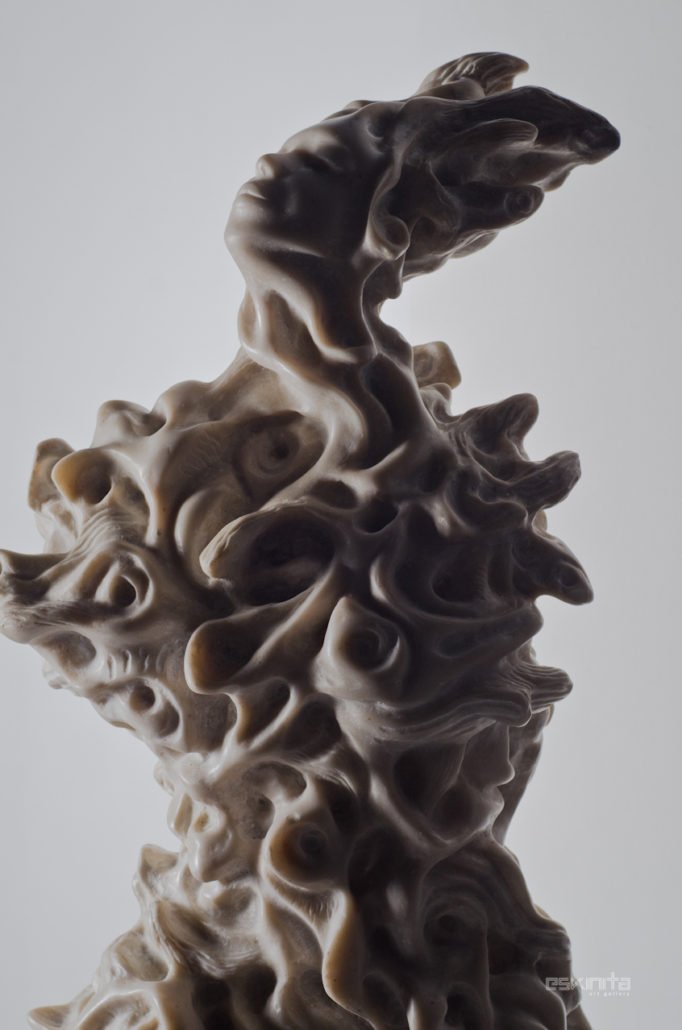

Certainly, there is a tendency for the mentee to replicate the style, the technique, or the theme of his mentor. While it is true that all of the eight artists work with and/or around social issues, it is evident that they’re coming from different vantage points and employing their respective visual registers. Take, for example, Harry Mark Gonzales and Carlo de Laza, who are the two sculptors of the group. Both working with the imagery of water, Gonzales approaches it from a more tactile level, evoking its waves and ripples in an almost abstract form while de Laza, on the other hand, who has a more figurative bent, uses water to explore a variety of psychological issues.

Both evoking death in their works, Michelle Ballesteros, a born-again Christian whose belief system prohibits her from painting religion icons, uses it to raise questions about faith, the story of the incarnation, and the notions of the hereafter. Marvin Quizon’s approach, in contrast, draws resolute attention on death’s appearance in the natural world. Contrast is present too in the works of Mark Leo Maac and Isko Andrade. Where Maac’s figuration evokes the use of light as a transformative element as well as the illusion of (slow) motion, Andrade’s, meanwhile, tries to capture the stillness of a figure resting on the ground swaddled in shadows.

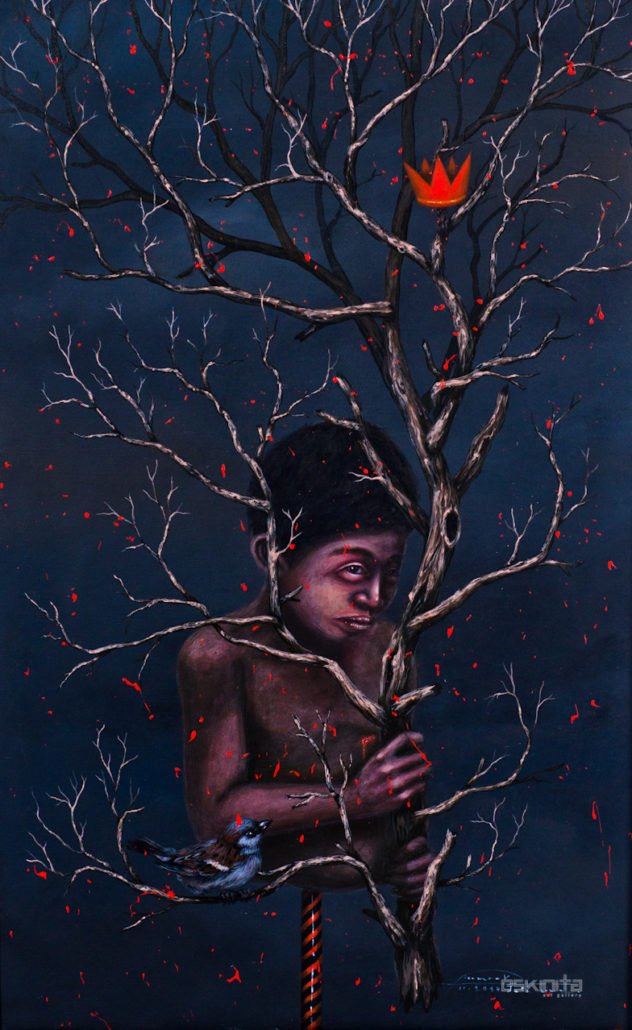

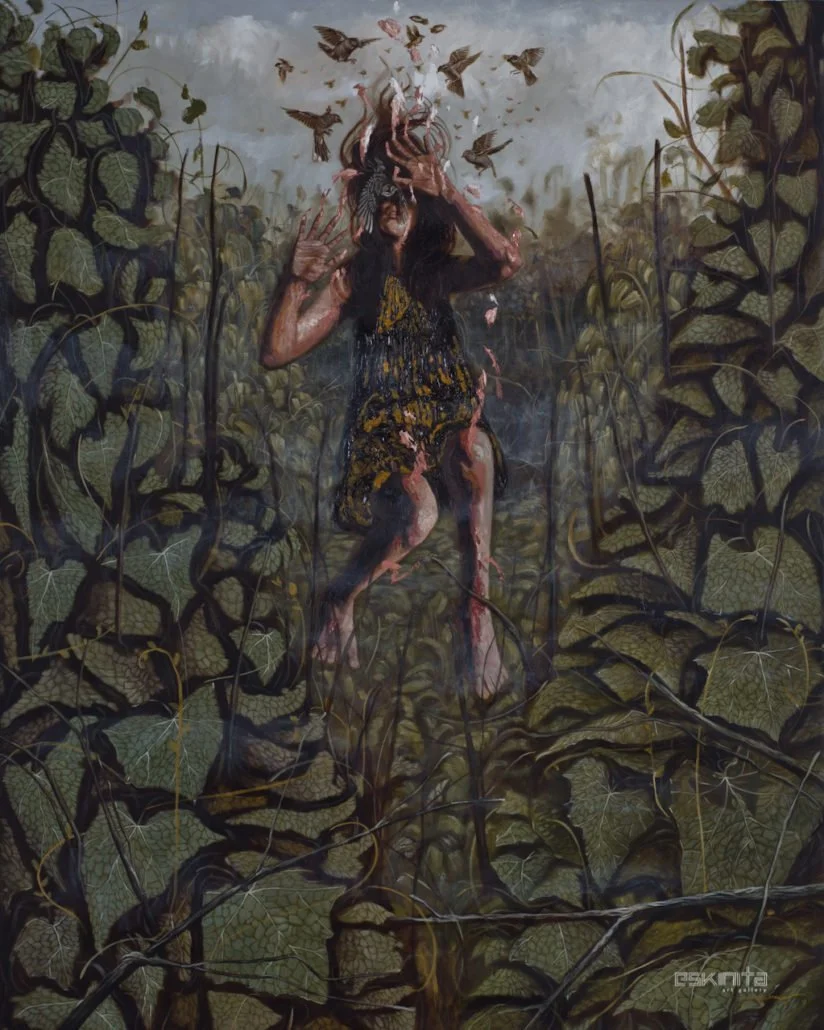

Finally, Denmark Dela Cruz and Lawrence Cervantes work in the vein of the surreal, with their works teeming with objects and beings from the natural world while attempting to capture imbalances and instabilities. Dela Cruz deals with social issues through visible dichotomies (the proletariat versus the oligarch) as well as his use of the crown, which symbolizes the deployment—and possibility—of power. Poetic and subtle, the works of Cervantes are a commentary on painting itself. He covers part of his subjects’ faces with a riot of birds and impasto applied with a palette knife in a radical act of defacement.

One may, of course, draw parallelisms and departures across other combinations of artists, but what will remain evident is the multiplicity of concerns refracted through their individual sensibilities. In this group exhibition, what binds them is a less visible, but no less important, string: their commitment to convey deeply felt realties. As Eskinita Gallery launches them formally through this show, we hope that they will embark on their own discovery as well. Cliché as it may sound, this exhibit is just the start of a life-long journey, but the seed has been planted and, in fact, has broken through the light.

–Carlomar Arcangel Daoana